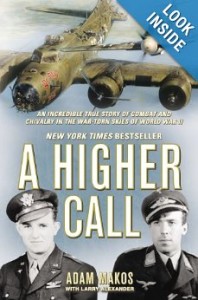

For many reasons, such as its jaw-dropping, mid-air action sequences and historical significance to humanity, just to name a few, I think that “A Higher Call” is an award-winning movie waiting to happen.

Its author, Adam Makos, and I have something in common, sort of, in terms of going beyond the boundaries that each of us, respectively, had set for ourselves and benefiting from the experience. In the process of documenting the story, he matured tremendously as a human being; and so did I from reading his book.

Its author, Adam Makos, and I have something in common, sort of, in terms of going beyond the boundaries that each of us, respectively, had set for ourselves and benefiting from the experience. In the process of documenting the story, he matured tremendously as a human being; and so did I from reading his book.

As the author was growing up and very much interested in interviewing and writing the stories of WWII veterans, he and his friends made a pact that they would never interview the “enemies.” His original focus, therefore, was strictly on American WWII veterans. Yet, the hero of “A Higher Call,” Franz Stigler, was a German fighter pilot, America’s former enemy. The author was introduced to Franz by Charlie Brown, an American B-17 bomber pilot. Charlie told the author that if he wanted to write about Charlie’s WWII experience, he would need to talk to Franz first because Franz was the real hero, to whom Charlie, his crewmen, and their descendants owed their lives. And so it goes – the majority of the book focuses on Franz, his background, his character, and what made his story so extraordinary.

Because of the time constraints, I consciously limit the scope of projects with which I get involved – including the books I choose to read about WWII. This means, normally, the books I pick up are focused solely on events that took place in the Pacific Theater. In fact, I have never read anything specific on the European Theater. Yet, when David (my husband and best friend of 41 years) told me about “A Higher Call,” I was instantly drawn to it. I had to make an exception and read it for myself. And am I glad I did!

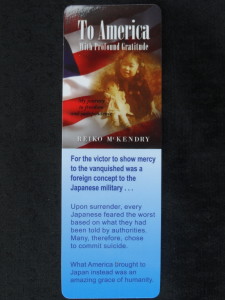

For me, coming to America has been a journey to becoming a better human being, one small step at a time. I wanted to be just like Americans, all of whom I perceived to be “good” people when I was growing up in Japan. By the time I became a naturalized U.S. citizen at age 37, I was cognizant, at least in theory, of the fact that it would be a mistake to generalize about a group of people – whether based on national origin, race, etc. – as having definitive traits and/or characteristics, either good or bad. Anywhere in the world, each individual is unique and different. Yet, in practice, the book made me realize how I was still generalizing about some groups of people, such as the Germans, as a whole. I found this generalization of others rather disconcerting. Why?

It relates to how I have been concerned about how the Japanese, as a whole, may still be perceived by many Americans – particularly by those who experienced WWII directly or indirectly. This was one of the major reasons I felt compelled to write my autobiography. My concern is based primarily because Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 was such a pivotal moment in the history of the United States. In fact, when Al Qaeda attacked the twin towers on September 11, 2001, the aggression was invariably compared to the attack on Pearl Harbor some 60 years prior.

It is an understatement to say that the atrocities inflicted on millions of people by the Nazis in Europe – much like those by the Japanese military, primarily in Asia – were horrendous. They were so evil that most people, at the time, could not fathom humans were capable of such dastardly deeds. Today, most of us do know that it is indeed within the realm of human capabilities.

When conditions are ripe, a dictator emerges as a “savior” to a nation full of people in despair. Somewhere toward the end of the book, Franz said he had seen the (Nazi) Party turn Germany into a place where a person could be killed for telling a joke. He wondered, “Had the Party gone from incarcerating its opponents in 1934 to slaughtering them in 1944? The idea no longer seemed far-fetched.” That was a span of merely a decade before the freedom of every human being was being threatened under Hitler’s regime. Because of such historical lessons, many of us in the United States today have healthy doses of skepticism about our country’s officials and their behaviors – even though, much like in Germany in the 1930s, the “majority” voted them in to their positions of power as “public servants.” Is the current level of skepticism enough to prevent another Hitler-like evil, disguised as a godsend in the minds of desperate millions, from rising to absolute power? Only time will tell.

One of the best parts I liked in the book was when Franz said to one of his colleagues that he was done with the notion of following orders. He had seen what “following orders” had done to Germany. Having lived through the culture and tradition of blind obedience to superiors within a hierarchy myself, where people are discouraged from questioning authority in the name of harmony (both in Japan and, believe it or not, in the United States as well), I can relate to Franz’s sentiment. Amen to freedom.

Postscript: Thanks to the video technology, we are able to watch an interview of Franz Stigler and Charlie Brown. It is priceless.